Difficult Books,

or:

The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge

Yesterday, I Facebook-posted a link to a recent Publisher’s Weekly list of ‘The Top Ten

Most Difficult Books.” It’s

actually a smushing-together of two five-item lists from PW contributors, which helps account for its perplexing

nature. But not fully. Here’s the list:

--Nightwood,

Djuna Barnes

--A

Tale of a Tub, Jonathan Swift

--Phenomenology

of Spirit, G. F. Hegel

--To

the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf

--Clarissa,

Samuel Richardson

--Finnegan’s

Wake, James Joyce

--Being

and Time, Martin Heidegger

--The

Faerie Queene, Edmund Spenser

--The

Making of Americans, Gertrude Stein

--Women

and Men, Joseph McElroy

(Link to full article, which includes ‘explanations’ of why

the contributors selected these particular books: http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/book-news/tip-sheet/article/53409-the-top-10-most-difficult-books.html#comments)

The Difficult Books list makes little sense because it is

not based on an agreed-upon definition of what ‘difficult’ means when it comes

to books. ‘Difficult’ because the

language is complex and playful and linguistically demanding (Finnegan’s Wake, The Tale of a Tub)? ‘Difficult’ because the allusions and

intertexts require specialized knowledge (The

Faerie Queene, The Tale of a Tub)? ‘Difficult’ because the book is very

long and bulky and thus physically hard to read unless you have a Kindle, not

to mention the problem of keeping characters and event sequences straight (Clarissa, Women and Men)?

‘Difficult’ because the style or point-of-view is self-consciously

experimental (To the Lighthouse, Nightwood, The Making of Americans)? ‘Difficult’ because the book in

question is a philosophical treatise translated from German (Phenomenology of Spirit, Being and Time)? Or, as one of my friends so astutely and

sarcastically commented, ‘difficult’ because the work is morally disgusting (“I

thought Clarissa was hard to read

because the protagonist was abducted and raped into anorexia”)?

What we have with the PW

Difficult Books list is a wonderful example of the ill-posed question (tacit in

this case: ‘what are difficult

books’ cannot be answered without first defining ‘difficult’) that generates category

confusion and subsequent logical chaos.

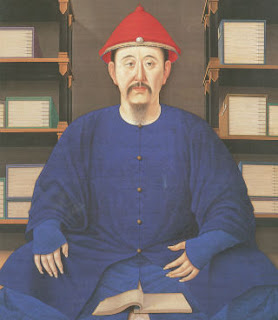

The best example of category confusion I know can be found in The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent

Knowledge, a nonexistent treatise invented by Jorge Luis Borges in his 1942

essay, “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins.” The fictional Chinese encyclopedia classifies animals in the

following way:

- those that belong to the Emperor,

- embalmed ones,

- those that are trained,

- suckling pigs,

- mermaids,

- fabulous ones,

- stray dogs,

- those included in the present classification,

- those that tremble as if they were mad,

- innumerable ones,

- those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush,

- etcetera,

- those that have just broken a flower vase,

- those that from a long way off look like flies.

This delightful piece of nonsense (I know – Michel Foucault

and George Lakoff find it profound) illustrates by omission the requirements

for constructing a ‘scientific’ classification scheme: the categories must be sufficient (they

must accommodate all examples) and mutually exclusive (an example should fit

into one category only; this is why classification schemes are usually branched

and subdivided, so ultimately there’s only one appropriate category per item). It also demonstrates the seductive power

of lists (their very existence, plus their spatial ordering, conveys a

presumption of fact, so we want to make sense of them.)

Returning to the list of Difficult Books: a coherent list could be created from

any of the meanings of ‘difficult’ mentioned above. But even with a reasonable working definition, the problem

of circumscribing the set of possible entries remains. This is an issue more rightly belonging

to common sense than to classical logic.

--It doesn’t make sense to clump fiction with non-fiction

(particularly philosophy) when it comes to difficult reading. So let’s throw out non-fiction.

--It’s probably not fair to author or text to judge

translations on a ‘difficulty factor.’

So (since I’m writing in English to an English-speaking audience), let’s

jettison translations into English.

--The ‘difficulties’ of poetry are distinct (at least in

part) from the ‘difficulties’ of prose.

Let’s bid adieu to poetry.

--To make a list for a general audience’s consideration (or

at least an audience larger than the list-generator herself), there should be

some consideration of familiarity.

Who would care about a list of ‘Difficult Incunabula That Almost No One

Has Ever Read’? In the case of our

new and improved ‘Difficult Books’ list, I suggest adding a restrictor along

the lines of ‘books considered as classics/commonly included in academic curricula’ (not a restrictor immune from debate,

seeing as how the vexed word ‘classic’ is included, but one has to start

somewhere).

Now we’re beginning to have a sensible list definition: ‘Difficult Classic Prose Fiction

written in English.’ Once we agree

on what we mean by ‘difficult,’ we’re ready to take the short bus to list-land.

The linguistically difficult list would be pretty easy to

compile and I suspect would generate a fair amount of agreement. We could start with a couple from the PW list and add to them:

--Finnegan’s Wake, James Joyce

--The Tale of a Tub, Jonathan Swift

--Sartor Resartus, Thomas Carlyle

--Ulysses, James Joyce

--Sosa Boy, Ken Saro-Wiwa

--Sea of Poppies, Amitav Ghosh

--Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pyncheon

--Pale Fire, Vladimir Nabokov

--Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Caroll

--White Teeth, Zaydie Smith

But what if we define difficult as ‘a massively arduous

reading experience with meager rewards’ ?

To get us started:

--Clarissa, Samuel Richardson

--Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand

--The Temple of My Familiar, Alice Walker

--Sir Charles Grandison, Samuel Richardson

--The Golden Bowl, Henry James

--The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, J. R. R.

Tolkien

--The Wings of a Dove, Henry James

--Ancient Evenings, Norman Mailer

--It, Stephen King

--News From Nowhere, William Morris

Additions?

Deletions? Arguments? Chastisements for ignoring political

prevarications, domestic terrorism, and international upheaval in favor of the

easy pastime of list-analysis and list-making? Well, I’ve been busy with The

Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Sports, London 2012 edition, which

classifies sports in the following manner:

1. Sports

where athletes wear sunglasses

2. Dancing

horses

3. Dancing

gymnasts

4. Sports

where you can’t use your hands

5. Sports

judged subjectively

6. Sports

where, to win, you move in exactly the same way as another person

7. Kayaks

8. Sports with

six-letter names

9. Sports

where, to win, you move faster or higher than another person

10. Rifles

11. Sports

where athletes wear protective headgear

12. Sports

that no one from the Caribbean has ever won

13. Sports

where the apparatus can kill you if it falls on you

14. Sports during which fans dress up like eagles

14. Sports during which fans dress up like eagles

15. Sports

that make you laugh

Enough lists for now.

It’s almost time for the medal rounds of a sport where athletes wear

sunglasses.

No comments:

Post a Comment